by Marcy Herr

(Pictured in front of the Ministry of Education: Jason Whitney, Eric Tarosky, Jennifer Lee, Hanna Mincemoyer, Catherine Johnson, Marcy Herr, Conor Searles, Paul Penkal)

I really enjoyed having the opportunity to have a discussion with Joselita Júnia Viegas Vidotti, International Adviser, and Paulo Alves da Silva, high-level Administer in the Departamento de Políticas de Educação Infantil e Ensino Fundamental (Pre-school and Elementary Education). As Mr. da Silva spoke, I couldn’t help but think that the U.S.’s strong educational system is being sidetracked by misguided policies that place too much much emphasis on the standardization of curriculum and teaching to the test, and that Brazil is making some very good moves.

(Pictured from left: Conor Searles, Marcy Herr, Cristina Dale, Hanna Mincemoyer, Catherine Johnson, Jennifer Lee, Edson Machado background)

(Pictured from left: Conor Searles, Marcy Herr, Cristina Dale, Hanna Mincemoyer, Catherine Johnson, Jennifer Lee, Edson Machado background)

In Brazil, progress in education is evident. A good first step was the in the 1996 Right to Learn policy. This allows students the right to determine what they would like to learn to a certain extent. The Right to Learn policy requires that teachers follow the national curriculum guidelines, while at the same time providing them the freedom to teach what their students are most interested in. This allows for flexibility in curriculum that can include teaching about specific values that vary due to the extraordinary diversity of regional culture in Brazil.

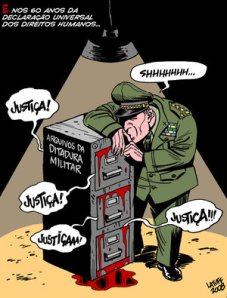

An issue that has been seen in the implementation of this policy is a hesitation of Brazilian teachers and schools to take ownership over their curriculum and instruction. Due to the history of a military regime in Brazil, for many teachers it has become habit to rely heavily on the federal government and to be told what to teach. Historically, this reliance on the government stemmed from a fear of going against the regime, but a cultural shift must occur today in order to help the Brazilian schools move away from this attitude. There is great potential for Brazilian teachers to be flexible once they become comfortable with this high level of ownership and freedom over their classroom.

At the same time that Brazil is encouraging teacher creativity in their curriculum, the U.S. is unfortunately moving towards the opposite: Teaching to the test, or implementing a common core curriculum is encouraging national uniformity and standardization, reducing teacher autonomy and de-skilling teachers. Such homogenization of curricular materials is bound to make it more difficult for students to connect to and recognize the value of their learning.

(Pictured from left: Joselita Júnia Viegas Vidotti, Paulo Alves da Silva, Edson Machado, Jason Whitney)

(Pictured from left: Joselita Júnia Viegas Vidotti, Paulo Alves da Silva, Edson Machado, Jason Whitney)